The Mobile Revolution vs. The AI Revolution

.avif)

.avif)

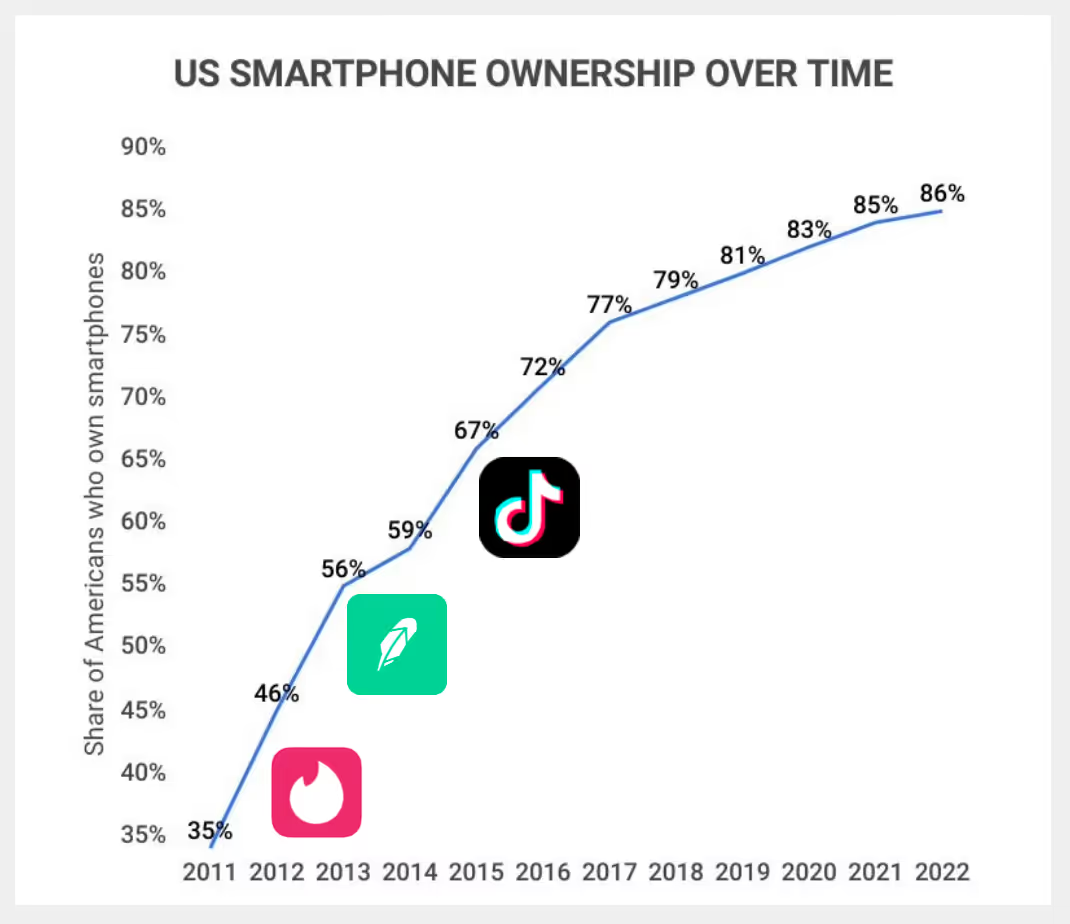

The iPhone launched in 2007, and within a few years it sparked the mobile app boom, Uber was founded in 2009, WhatsApp in 2009, Instagram in 2010, Snap in 2011. These success stories didn’t happen overnight; they emerged years after smartphones went mainstream. The lesson from the mobile revolution is that transformative technology waves take time to unfold. Today, with all the buzz around artificial intelligence (AI), it’s worth asking: will the AI revolution follow a similar trajectory, or is it a different beast entirely?

Despite the current hype, AI’s adoption is still in early innings. In the United States, for example, 58% of adults had heard of ChatGPT by mid-2023, but only 18% had actually used it. In fact, after an initial surge of curiosity, ChatGPT’s user growth even dipped slightly over last summer. This suggests that truly game-changing “killer apps” for AI are still on the horizon, just as the mobile era had to wait a while for its defining applications. Many of those AI applications are being dreamt up right now. As we’ll explore in this article, the AI revolution is poised to be bigger than the mobile revolution: more comparable to the dawn of the internet itself in its scale and impact. In short, the “Information Age” that began in 1971 may be reaching its finale, and a new era of AI is beginning. Let’s dive in.

When you’re in the middle of a technological upheaval, it’s hard to gauge its true impact. That’s why history is full of very poor tech predictions. For example, economist Paul Krugman famously wrote in 1998, “By 2005, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.” – a statement he’s had to live down for decades. Ouch. In moments like this, it helps to zoom out and look at patterns from previous technology cycles.

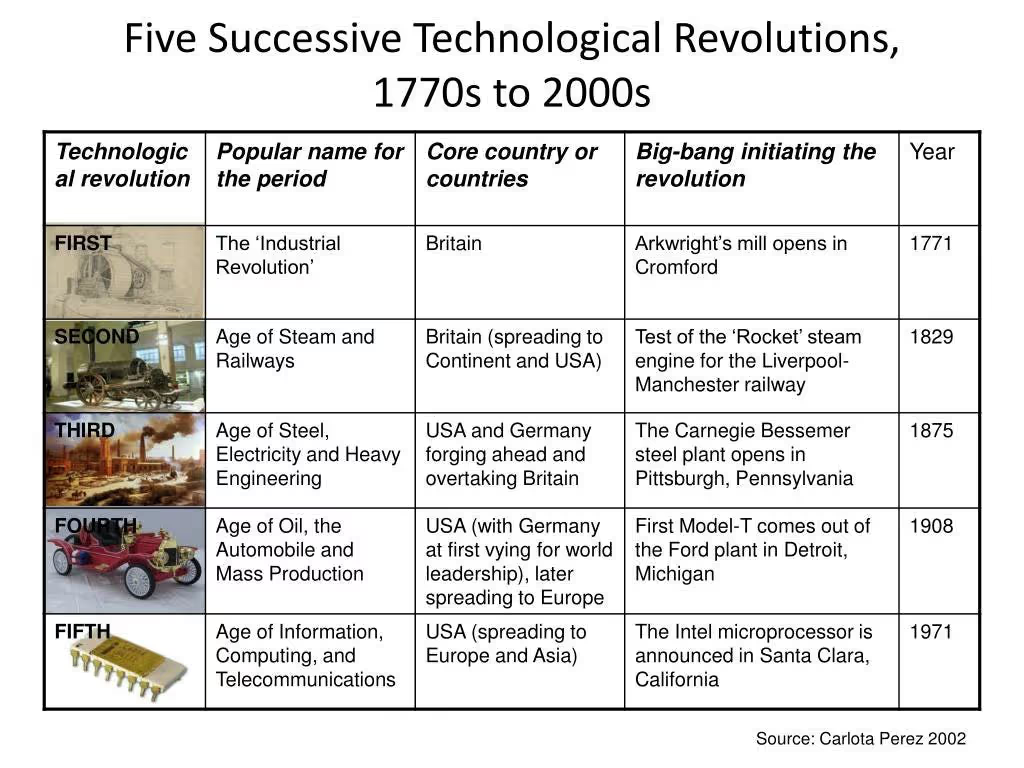

Economist Carlota Perez did exactly that in her study of the past 250 years of innovation. She identified five major technological revolutions since the late 18th century. Each was ignited by a “big bang” breakthrough that set off a wave of change. For instance, the Industrial Revolution of the late 1700s was sparked by mechanised textile mills; the Age of Steam and Railways began around 1829 with the spread of steam engines and railroads; later came the age of steel and electricity in the late 19th century, then the age of oil, automobiles and mass production in the early 20th century. Our most recent revolution, the Information Age, started in 1971 when Intel produced the first commercial microprocessor. Silicon microchips would give “Silicon Valley” its name, and the rest is history.

Each of these revolutions tends to follow a similar boom-and-bust rhythm. A thrilling new technology appears and attracts frenzied investment, which leads to a speculative bubble; the bubble eventually bursts, wiping out the hype. But that crash often marks a turning point rather than the end. Perez observed that about halfway through each ~50-year cycle, a major crash or turning point occurs (think of the 1840s railway mania or the 1999–2000 dot-com bubble). After that, the technology enters a deployment phase: roughly two decades of steady growth, when the technology truly transforms economies and everyday life. In the case of the internet, after the dot-com bust in 2000, the 2000s and 2010s saw the real Golden Age of the web, with widespread adoption of the internet accelerated by mobile and cloud computing. With the benefit of hindsight in 2023, Perez’s framework appears spot on.

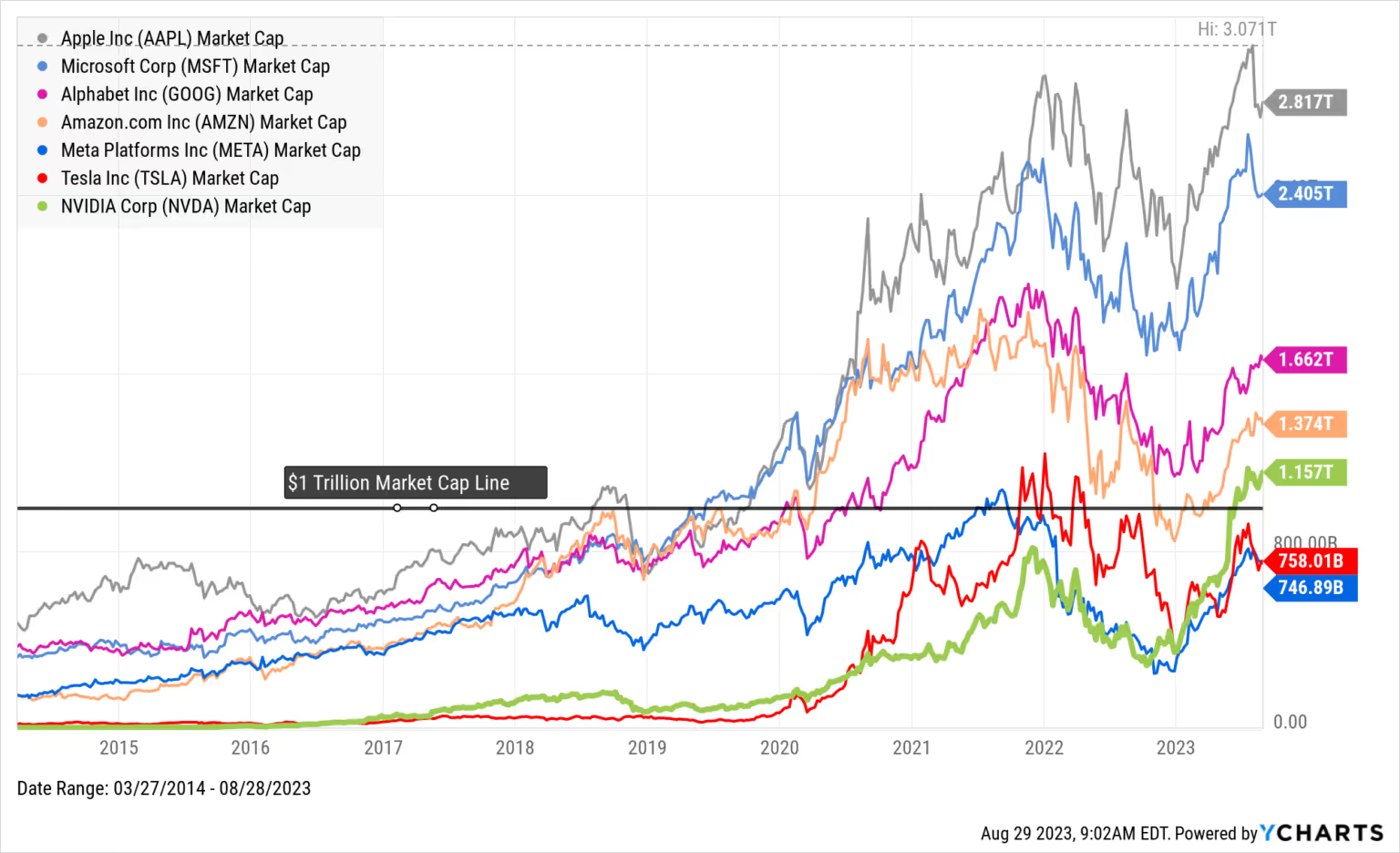

We can see these cycles in the changing of the guard among dominant companies. In the 1930s and ’40s, during the Age of Oil and mass production, giants of oil and automobiles overtook the old steel and railroad empires. Fast forward to 1990: the world’s top companies by revenue were still industrial titans – not a tech company in sight. But today, the list is dominated by tech behemoths. Apple, Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Amazon, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Meta are among the most valuable companies on the planet. (Apple alone raked in about $394 billion in sales last year, with a whopping 25% profit margin.) By late 2023, Big Tech companies made up nearly 30% of the S&P 500 index’s value – an astonishing concentration of economic power in a handful of firms.

Paradoxically, this very dominance is a sign that the current technological paradigm is maturing. Once a revolutionary technology becomes ubiquitous and incumbent firms reign supreme, the space for explosive new growth narrows. In other words, the Information Age – the era of computers, the internet and mobile – is hitting its saturation point. Technology is everywhere, and that’s amazing, but it also means the revolutionary edge of the last cycle is dulled. History tells us that when one revolution reaches its limits, the next revolution is usually around the corner.

New technology revolutions tend to emerge when the potential of the previous one is largely tapped out. And by the mid-2020s, many in tech felt we were at that exhaustion point. Venture capital was abundant over the last decade, but it was increasingly chasing incremental ideas and “point solutions”. Truly massive breakthroughs (the kind that spawn hundred-billion dollar companies) were getting rarer. How many startups founded since 2016 can you name that reached $100 million in annual revenue? Aside from a short list (e.g. Wiz, Ramp, Deel, Rippling), there haven’t been many. The app stores aren’t producing smash-hit new apps like they did a decade ago. Big Tech firms like Alphabet and Meta have started to show their age, slowing down and oozing bureaucratic arthritis. Investors and innovators alike were thirsting for the next seismic shift.

Thankfully, we have one: AI. The timing of AI’s rise is nearly perfect according to Perez’s cycle. For the AI revolution, the “big bang” moment was arguably the public release of ChatGPT in late 2022. (You could argue the spark was lit earlier – say, the 2017 research paper introducing transformer neural networks – but ChatGPT was the moment AI burst onto the world stage in a big way.) Consider this: ChatGPT reached an estimated 100 million users just two months after launch, making it the fastest-growing consumer application in history. For context, it took TikTok about 9 months to hit that milestone, and Instagram over 2 years. This kind of instant adoption is unprecedented – a clear sign that AI is a revolution with momentum.

Another hallmark of a new tech era is talent migration, and we’re seeing that too. Top researchers and engineers are leaving comfortable jobs at mature tech companies to pioneer the AI frontier. The co-author of the seminal “Attention Is All You Need” paper (which paved the way for modern AI models) left Google to start an AI company. Teams from Google Brain, Meta, and other giants have spun out to launch AI startups like Cohere and Ideogram. This brain-drain from incumbents into new ventures is reminiscent of earlier shifts – it’s exactly what happened when, say, early internet startups lured talent away from 90s conglomerates. It’s a sign the centre of gravity is moving.

If we zoom out, the past 50 years of tech progress line up neatly with Perez’s framework. To oversimplify: the 1970s–80s were the “irruption” phase, when venture capital emerged and turbocharged the nascent computer industry. The 1990s saw a speculative frenzy (and yes, things got ahead of themselves during the dot-com mania). The early 2000s through mid-2010s were the deployment or “synergy” phase – the Golden Age of the internet, with steady growth and massive wealth creation, boosted further by mobile and cloud tech. The late 2010s to now marked maturation. The dot-com crash of 2000 and even the 2008 recession and 2020 pandemic disrupted the timeline a bit, but overall the pattern held. And now here we are in Phase One of a new revolution, witnessing explosive AI innovation at the dawn of a fresh cycle.

This is exciting. In fact, the very comparison in the title of this piece – Mobile vs. AI – is a bit of a misnomer. The AI revolution isn’t just another chapter in the mobile/web saga; it’s something much bigger. AI represents a more fundamental shift in technology’s evolution. If anything, the mobile revolution was a smaller “distribution” revolution (putting the internet in everyone’s pockets). AI, however, is about changing the very nature of computing and problem-solving. One way to think about it: we’re moving from the calculator era to the brain era. Read more about our take on The Platform Shift here.

Back when electronic computers were first conceived, there was debate over whether they should mimic simple calculators or mimic human brains. Due to technical limits, the “calculator” approach won – computers were designed as literal, logical number-crunchers. They turned out to be excellent at computation, but not so great at things like creativity, context, or common sense. Now that’s changing. AI is making computers much more brain-like – capable of tasks that once belonged solely to humans. In fact, AI systems today outperform people at a growing list of skills: reading comprehension, image recognition, language translation, and more. In one medical study, ChatGPT not only answered patients’ questions more accurately than doctors did, but it was also rated as having a better bedside manner. (It turns out AI doesn’t get tired or irritable, unlike human physicians!) Computers used to be just number crunchers; now they can write stories, draw artworks, compose music and even crack jokes. In short, machines are learning to be creative and empathetic.

Naturally, this new epoch will bring with it new opportunities for innovation. We’re at the cusp of an AI age that promises to reshape industries and create avenues for wealth and progress – just as past revolutions did.

Every technological revolution unlocks a wave of opportunities, and AI will be no exception. We can already see the first sprouts of innovation appearing. Some of these opportunities are extensions of what came before, some are entirely new capabilities enabled by AI, and some will be surprising offshoots in adjacent areas. Let’s break down a few ways this could play out:

These are ideas that carry forward concepts from the mobile/internet era and inject them with AI. We’re seeing entrepreneurs build “Instagram for AI”-type apps, for example – tools that let you create and share AI-generated images of yourself and friends in fantastical scenarios, just as Instagram lets you share photos. There’s talk of a “Pinterest for AI” – imagine a platform where all the interior design inspirations or fashion ideas you scroll through are AI-generated on the fly. Generative AI can provide endless content, so it’s natural to envision social or creative apps built around this new “infinite canvas.” Of course, any AI-native upstart that looks like “the next Instagram” or “the Canva of AI” will face an immediate challenge: incumbents are not standing still. Established platforms have already begun layering AI features into their products. (Canva, for instance, quickly added AI image tools.) Will a new AI-based social app really dethrone an incumbent that adapts to AI? It won’t be easy – but history shows incumbents don’t always get it right, leaving gaps for newcomers to exploit. Only time will tell who wins those battles.

These are the opportunities that exist only because of the new technology’s capabilities. Think of businesses that were impossible before AI came along. For analogy, Uber could only emerge thanks to smartphones with GPS – without mobile tech, the idea of tapping a phone to summon a ride in minutes was unthinkable. Snapchat became a multi-billion dollar company by leveraging the smartphone camera and touch-screen to create ephemeral, visual messaging that never existed before. In the same way, AI will enable startups and solutions that we can barely imagine right now. With generative AI, it’s becoming dramatically faster, cheaper, and easier to create any form of digital content – text, images, videos, code. One observer neatly noted: “The internet blew open the gates of distribution; generative AI blows open the gates of production.” In other words, the web allowed anyone to distribute content to millions of people, and now AI allows anyone to produce content that would have taken armies of creatives or engineers to produce before. This could mean an explosion of AI-native businesses that fill all sorts of niches: automatically generating personalised education lessons, designing virtual worlds on the fly, tailoring marketing content to each customer, you name it. When technology gives everyone “creation superpowers,” expect some completely new and wild ideas to flourish.

One of the most fascinating aspects of big tech revolutions is how they spawn entirely new industries on the periphery. The ripple effects create markets that no one initially anticipated. For example, the automobile age didn’t just give us car companies – it led to suburban shopping malls and drive-thru restaurants, and even the credit card industry was boosted by mass car-enabled consumerism. The internet revolution, likewise, gave birth to industries like search engines and social media that now generate hundreds of billions in revenue (Google alone earned about $282 billion last year from its largely internet-based business, while Meta/Facebook brought in $116 billion. Who could have imagined in 1990 that “search engine” or “social network” would be massive industries of the 2010s? In the same vein, the AI revolution will have second- and third-order effects. We can already guess a few areas – for instance, industries around AI safety and ethics (ensuring AI systems are fair and secure), AI education and training (helping people learn to work with AI), or even creative new fields like AI-generated entertainment and virtual companions. The truth is, many future industries will only become obvious in hindsight. As AI technology matures, we’ll likely see entirely new markets spring up that today would sound like science fiction. The opportunities are vast, and some are yet invisible.

With so much activity, it’s inevitable that not everyone will succeed. Just as the Gold Rush had more prospectors than fortunes, the early AI startup landscape will be crowded and chaotic. We’ll probably witness dozens of “Uber-for-AI” or “Netflix-for-AI” ideas being tried. Separating the signal from the noise is going to be a challenge for investors and innovators alike. An anecdote from the mobile app boom illustrates this point: back in 2010, a leading venture capital firm had invested in a little photo-sharing startup called Instagram, but then decided to shift its attention and poured $5 million into a rival app named PicPlz, effectively betting that it would be the breakout success. We all know how that turned out – Instagram became a global phenomenon (later acquired by Facebook for $1 billion), while PicPlz disappeared with barely a whimper. Picking winners in a frenzy is hard. The same will be true in the AI arena: plenty of ambitious projects will launch, but only a few will reach the finish line as enduring companies. Cautionary tales like the Instagram vs. PicPlz saga will likely replay in the AI startup world.

While startups are scrambling to build the “next big thing” in AI, it’s important to remember that the AI revolution isn’t just for startups. It presents opportunities (and challenges) for every organisation – from scrappy new ventures to the largest enterprises and governments. AI is a general-purpose technology that can enhance almost any field of human endeavour. As such, the way existing organisations adapt to and adopt AI will be just as important as the rise of new AI-native firms. Key areas of focus include:

Embracing AI is quickly moving from optional to essential across industries. Companies are integrating AI to automate processes, gain insights from data, and create smarter products. As of 2024, about 78% of organisations worldwide reported using AI in some capacity, up from 55% just a year before– a testament to how rapidly AI adoption is accelerating. From factories using AI for predictive maintenance to hospitals using AI for faster diagnoses, adopting this technology can dramatically boost efficiency and effectiveness. Organizations that drag their feet on AI risk falling behind their competitors. The flipside is that adopting AI thoughtfully can be a huge competitive advantage.

To truly leverage AI, businesses and governments need a clear AI strategy. This means more than just experimenting with one-off AI tools. It involves identifying where AI can add the most value, setting concrete goals (like improving customer service via chatbots or optimizing supply chains with AI forecasting), and aligning AI initiatives with overall objectives. An AI strategy also covers the how – e.g. choosing whether to build AI capabilities in-house or use partners, how to manage data, and how to upskill employees. Without a coherent strategy, organisations risk dabbling in AI without ever reaping its full benefits. With a strategy, AI becomes a core part of the mission – much like having a digital strategy became crucial in the internet era.

As AI technologies proliferate, there’s a growing need for sensible AI policy and governance – both within companies and at the societal level. Governments are now drafting regulations and guidelines (such as the EU’s upcoming AI Act) to ensure AI is used ethically and safely. Companies, too, are creating internal AI policies to govern how they deploy AI in their operations (for example, policies on avoiding bias in AI algorithms, or rules for AI usage by employees). Good policy strikes a balance: it should mitigate risks like algorithmic discrimination, privacy breaches, or unsafe AI behaviours, without stifling innovation. Getting this right is tricky but crucial. Clear policies and frameworks build public trust in AI systems and provide stability, which ultimately helps the AI ecosystem grow. Just as we developed traffic laws when automobiles became widespread, we’re now crafting the “rules of the road” for the AI age.

The AI revolution comes with a steep learning curve, and not every organisation has AI experts on staff. This is driving demand for AI consultants and specialists who can guide businesses through the transformation. An AI consultant might help a retail company implement a recommendation engine, or advise a bank on using AI for fraud detection, or assist a government in formulating an AI deployment roadmap. These experts bridge the gap between what cutting-edge AI tech can do and the specific needs of an organisation. They can provide training, help set up AI infrastructure, and ensure that AI projects actually deliver value. In a time when there’s a shortage of AI talent, having experienced consultants can save companies from costly mistakes and accelerate their AI adoption. In short, they help organisations develop and execute their AI strategy effectively, and navigate the ethical and practical hurdles along the way.

Each of these areas – adoption, strategy, policy, and expert guidance – will determine how successfully organisations ride the AI wave. The companies that proactively adapt (upskilling their workforce, redesigning workflows around AI, engaging with policymakers, etc.) are likely to thrive. Those that ignore the shift may find themselves disrupted by those who don’t. AI isn’t just a new gadget; it’s a general-purpose capability that can supercharge almost any activity. The opportunity (and challenge) for everyone is to figure out how to integrate AI in a way that makes their products, services, or operations vastly better.

The economist Joseph Schumpeter famously described capitalism as a “process of creative destruction,” a “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionises the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” In plain terms: capitalism’s constant innovation means new technologies relentlessly replace the old. Nowhere is this more evident than in the tech industry, which is both an engine and a product of capitalism’s churn. Innovation is the spark of progress, and technology is its fuel. Each revolution doesn’t just add new things – it also renders old things obsolete. The AI revolution will be no different. It will create tremendous new value, but it may also upend companies, job roles, and even entire industries that fail to adapt.

Think about how far we’ve come in the current Information Age. In 1956, an IBM engineer proudly unveiled a 1-terabyte hard drive – it was the size of a 40-story building and incredibly costly. Today, a 1 TB drive fits in your pocket (or onto your fingertip, in the form of a tiny microSD card). Computing power has followed Moore’s Law, doubling every couple of years, leading to exponential improvements in price-performance. Technologies that once were national-lab curiosities (speech recognition, for instance) are now free on your phone. This dramatic progress has created whole industries and destroyed others. Typewriters gave way to word processors; film cameras to digital cameras, and now smartphone cameras have largely killed the point-and-shoot camera market. The cycle of creative destruction is continuously at work.

As we noted, the maturation of the Information Age has some painful side effects for those who invest in growth. Recently, we’ve seen a harsh market correction in the tech sector. In 2022, many public tech stocks plunged – some lost around 70% of their market value from their peaks. Lofty startup valuations from the boom times are coming down to earth. A unicorn that raised money at a $10 billion valuation might really be worth only $3 billion today, and a host of once-prized “future unicorns” have had to slash their valuations to find buyers. This kind of shake-out is a normal part of the cycle; it’s analogous to the dot-com crash cleansing the excess of the 90s. Overpriced companies will either reset or die out.

On the flipside, the dawn of a new technological era is great news for innovators and investors focused on the future. If the late stage of a revolution is tough for incumbents clinging to yesterday’s metrics, the early stage is fertile ground for newcomers. We’re at the dawn of a new era with AI, and as big companies tighten belts and some old ventures falter, a wave of fresh talent and ideas is being unleashed. Engineers leaving a stagnant Big Tech firm or an overhyped startup might become the founders of the next Google or Tesla – but in an AI context. In the venture world, many investors are refocusing on seed-stage bets, backing bold AI ideas that could be the Apple or Amazon of the AI age. The coming years will likely see an explosion of experimentation. Not all of it will succeed, but some will – and those winners could redefine the economic landscape.

It’s worth keeping in mind Amara’s Law, which says that we tend to overestimate a new technology’s impact in the short run and underestimate it in the long run. AI today might be a bit over-hyped in some quarters – there’s no shortage of grand claims, and indeed, not every AI startup with a sky-high valuation will pan out. We may very well see a couple of hype-driven mini-bubbles and corrections in the next few years. (If Perez’s framework holds, a big “turning point” correction could occur at some point during this AI cycle.) However, those inevitable bumps won’t detract from AI’s long-term potential. The transformative changes AI will bring over the next few decades are likely to far exceed what most of us today anticipate. Just as the internet eventually exceeded even the wildest 1990s expectations (who back then imagined a smartphone economy or cloud computing?), AI’s true impact will unfold over time and in ways we’re only beginning to glimpse.

One open question is where the value will accrue in the AI revolution. In past revolutions, often it was upstart companies that displaced the old guard (think of how Google and Facebook rose while earlier giants like AOL or Yahoo withered). But this time, the context is different. We are entering the AI age with several trillion-dollar tech incumbents firmly in place, and these giants are very aware of AI’s potential. In fact, Big Tech has been unusually quick to respond to the AI wave – perhaps having learned a lesson from history, they are determined not to be left behind. Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, Apple – all have announced major AI initiatives, from deploying advanced AI in search and productivity tools to launching AI platforms of their own. Traditionally, entrenched incumbents are hesitant to embrace radical innovations (because doing so can undermine their existing profitable businesses). But maybe this time is different, as tech firms aggressively pivot to AI so as not to miss out. The big question is: will the incumbents successfully seize most of the AI opportunity, or will new AI-native challengers rise up and usurp them? It’s too early to say. It’s possible that today’s tech giants will maintain their dominance by absorbing or outcompeting AI newcomers. It’s also possible that in 20 years, some of those giants will sound as dated as names like AOL or Nokia do today. The only sure bet is that change is coming, one way or another.

Finally, it’s interesting to reflect on the arc of the past half-century. The internet, mobile, and cloud computing each felt like huge revolutions – and they were – but you could also view them as successive waves within the broader Information Age. They were interrelated booms that all centered around computing technology and connectivity. Now, with AI, we aren’t looking at just another wave in the same cycle; we’re likely at the start of an entirely new technological revolution on Perez’s map. These kinds of revolutions don’t come around often – maybe once in fifty years or so – but when they do, they reinvent the world. The mobile revolution changed how we communicate and access information; the AI revolution could change how we think, decide, and create at a fundamental level. It’s a sea change that will touch everything from how businesses operate and how governments govern, to how we conduct our daily lives.

In other words, we’re in for one hell of a ride. The coming years of the AI revolution will be thrilling, occasionally turbulent, but certainly transformative. Just as smartphones and the internet are now taken for granted as foundations of modern life, AI is on its way to becoming an omnipresent force. History’s lesson is that those who recognise the magnitude of such revolutions – and adapt proactively – stand to benefit immensely, while those who ignore them risk being left in the dust of creative destruction. The mobile revolution reshaped the world over a span of 10–15 years; the AI revolution is now underway, and it could upend our world in even more profound ways. Buckle up and stay tuned – the journey has only just begun.